Justice Andrew Mutema of the High Court of Zimbabwe died on the 21st August 2015 and his remains were interred at the National Heroes’ Acre in Harare on 25 August , just a month and a half ago.

I do not usually care about who is buried at the national shrine or

who is denied a place there but with Justice Andrew Mutema I make an

exception, therefore I have penned this delayed obituary.

|

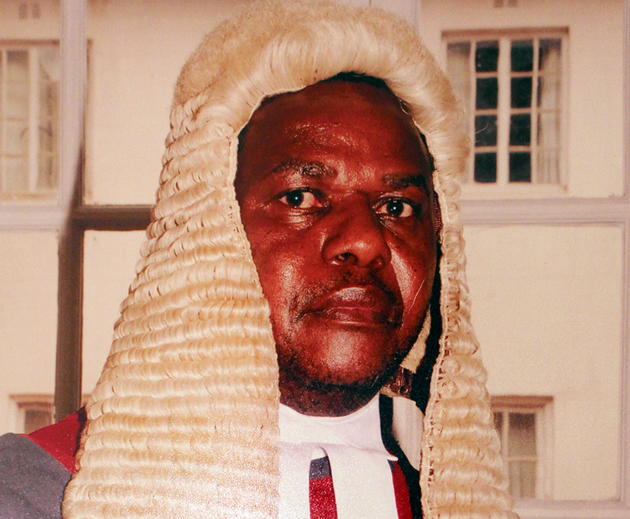

| The late High Court Judge Justice Andrew Mutema |

I was party to a case before him way back in 2012 as a student leader

and I witnessed some of his judgements that changed the lives of many

workers haunted by the Zimbabwe dollar era.

He was a judge par excellence, considering the era we are in where

political interests and impartiality of some of influential and powerful

members of our Zimbabwean bench have been regarded with suspicion in

many circles.

Concerning his life and death, Justice Mutema was a senior judge of

the High Court of Zimbabwe until the fateful day he collapsed at his

home and later died at the Mater Dei Hospital in Bulawayo.

He was born on 27 February 1959 and attended Silveira Mission in

Bikita, Masvingo Province. In his teenage years , he became a freedom

fighter and joined the Zimbabwean liberation struggle. His nom-de-guerre

(struggle name) was Kingsley Dube Watema.

He received military training in Mozambique and then, during the last

years of the struggle he was deployed to Romania for further military

training. After independence, he decided to pursue a career in the

judiciary.

He began as Assistant Magistrate in 1986 and moved up the ranks ,

becoming Senior President of the Administrative Court in 2004 and of the

Labour Court in 2007. He was appointed Judge of the High Court at

Harare 2010 and in 2013 became Senior Judge in charge of the High Court

at Bulawayo.

It was during his time at the High Court in Harare, that he decided

on a matter which had a direct effect on my personal and academic

development. But above all, the story of the judge’s life shows that

within the systems that oppress and exploit the majority of us, there

are good men and women, and because of these heroes we must celebrate

their ideals.

My encounters with the justice

A number of encounters made me come across the man himself as well as

the work of Justice Mutema. The most eventful encounter was a

make-or-break occasion for my academic and personal life.

|

| Kokerai Murombo, Tinashe Chisaira, James Katso and Gilbert Mtubuki during the days we awaited the court decision. |

I had just been elected SRC Vice-President at the University of

Zimbabwe (UZ) and on the eve of the inauguration, my main campaign

colleagues and myself were suddenly served with indefinite suspension

letters by the university over a campaign photograph that was supposedly

used by our campaign team from the Zimbabwe National Students Union in a

campaign newsletter.

The photograph featured the Vice Chancellor Prof. Levi Nyagura. My

fellow student activists who suffered the same misfortune were James

Katso who later contested in the Makokoba constituency elections in 2013

under a FreeZim Congress ticket; Zechariah Mushawatu, who contested in

the Harare East by-elections in June 2015 as an independent candidate;

Kokerai Murombo, who was later haunted from UZ and is now pursuing his

studies at the Wits University; then there was Gilbert Mutubuki, who is

now the president of the Zimbabwe National Students Union (ZINASU).

After we were issued with the letters we engaged lawyer Mr Obey Shava

of Mbidzo, Muchadehama and Makoni Legal Practitioners and a member of

the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights. The UZ Disciplinary Hearing ended

up with a deadlock and so we filed an urgent chamber application with

the High Court seeking to go back to school.

On a Thursday, the 10th of May 2012 we appeared in the

chambers of Justice Mutema at the High Court of Zimbabwe. The

university’s lawyer was there. Our key arguments were that we had no

case to answer and needed to get back to school to prepare for end of

semester examinations.

The university’s lawyer, a lady whose name I have forgotten, tried to

convince the judge that our papers were incorrect as we had claimed the

wrong starting dates for examinations.

The judge laughingly dismissed her, saying, “Come on, we have all

been to university. It doesn’t matter whether the exams are three weeks

or a month away. Students need to prepare for examinations.”

After that he, made an order lifting the suspension operating against

us pending the finalisation of the disciplinary proceedings. He further

ordered the University of Zimbabwe to pay costs for the entire court

application and that we be allowed access to lectures, tutorials,

library facilities as well as sitting for tests and examinations.

After issuing the order, the judge chuckled and faced us. He said ,”

You are young leaders, go to school and learn… But I am still wondering

how a whole Vice Chancellor would agree to pose for a photo with you,

ZINASU guys.”

That made us laugh and indeed our last sight of Justice Andrew Mutema

on that late afternoon in 10 May 2012 was that of a progressive,

reasonable and humorous judge.

The other encounters when I think of his great work, starts with the

time when I was Editor-in-Chief of the Kempton Makamure Labour Lecture

Series Board at the Faculty of Law, University of Zimbabwe (UZ).

I had to extensively review his Labour Curt judgements for

publication in the KMLLS Journal that was published in 2011 under the

theme “Legal and Constitutional Reforms on Indigenisation, Economic

Empowerment and Workers’ Rights” (ISSN 2223-5337).

The judgements however presented a man who was sometimes progressive

and sometimes not. In those days as well, the organisation I was working

with, called the Zimbabwe labour Centre, was handling a case in which

some former Flexi-Mail workers were claiming compensation in United

States dollars following the dollarisation era.

Precedent stated that people owed in Zimbabwean dollars had no basis

for being paid in US dollars because the Zimbabwe dollar was still legal

tender. On the ground, the local currency had become valueless and was

no longer acceptable anywhere in the country.

After a long struggle, it was Justice Mutema who ruled that it was

unjust to pay workers in Zimbabwean dollars in the US dollar era.

Fear for the higher courts

Fear over the setup and attitudes of the Zimbabwean bench is

justified, especially after the loss of people like justice Mutema is

justified. On 17 July 2015, exactly a month before Justice Mutema’s

death, the courts came up with the Zuva Petroleum decision, which in a few hours had altered the labour relations landscape in the country for the worst.

I criticised the implications of the decision, just a day or two later in an article that I wrote for Nehanda Radio.

The infamous decision condemned the working masses of Zimbabwe to the

punishment of a three month unilateral notice, and threw the issues of

collective bargaining and retrenchment benefits to the dogs.

The case made tens of thousands of Zimbabwean workers redundant

literally overnight. So in these circumstances it makes us mourn judges

like Justice Andrew Mutema more. And recognise that it was indeed fit

and proper for him to be interred at the National Heroes’ Acre.

Conclusion – Perceptions of a hero

The heroes of Zimbabwe are a contentious lot, at least most of them.

People have not been amused with how national heroes are selected by the

Politburo of the ruling party and not by any criteria set up in the

state legislation for example.

As responsible citizens it is helpful to keep that disgruntlement at

the back of our minds, but also not to taint all those interred at our

most famous burial site with the same brush.

Some of them are true heroes, who served their communities and their

people with a progressive spirit. If there is a book for such people, we

will surely add Justice Mutema’s name to the list without hesitation.

We are testimony to his heroic deeds and progressive judicial mind and I end up with quoting the words of William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar : “The evil that men do lives after them; the good is oft interred with their bones”.

Tinashe Chisaira is a lawyer and

activist and works for an environmental justice organisation in Harare.

He is a former student leader at the University of Zimbabwe and is a

Founder Trustee of ProJusticeZim, www.projusticezim.org , He tweets at @cdetinashe.

No comments:

Post a Comment